by Shira Sorka-Ram

I had the great privilege of knowing Ehud Ben Yehuda as a dear friend when I lived in Jerusalem in the early 1970s. I also knew his younger sister, Dola. Both were in their 70s. They were two of the three living children of Eliezer and his second wife, Hemda. The story of their father’s work and mission in life against unthinkable odds is both heartbreaking and heartwarming, and many books have been written about his accomplishments.

My purpose is to describe the struggle this family underwent to raise the Hebrew language from the dead. Their story is a huge life lesson for those called to accomplish something extraordinary. I will present this incredible story in a series over the next few months.

What kind of person does it take to single-handedly resurrect a language which had been dead since the second century A.D.?

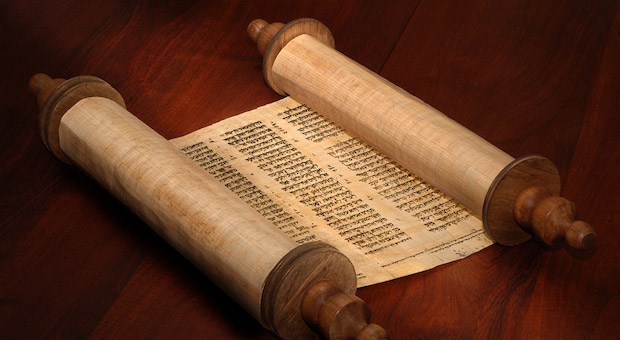

It is true that in the 19th century, there were a great many Jews who knew how to read the Torah and rabbinical books in Hebrew, or at least mouth the letters in the prayer book—especially in Eastern Europe. The ancient texts were chanted by religious Jews, but for the most part, barely understood. In Jerusalem there were a few Sephardic Jews (from Arab countries) who could even speak some Hebrew, but with a limited ancient vocabulary lacking all modern concepts. No one even considered that Hebrew could be a living language. Not one Jew spoke it as his mother tongue. For all practical purposes, the language was dead.

In the 1880s, there was a babble of many foreign tongues spoken by a grand total of some 30,000 Jews, who had come to the Holy Land from the four corners of the earth. Simply put, without Eliezer, it is doubtful there would have ever been a revival, literally, a resurrection of spoken Hebrew. Therefore, Eliezer Ben Yehuda bears the title of “The Father of Modern Hebrew” throughout the Jewish world.

Born in Lithuania in 1858, Ben Yehuda, the youngest in his family, learned the Hebrew Scriptures on his father’s knee. He loved spending time with his father, and with a phenomenal mind, at the age of 4, he already knew significant portions of the Torah, the Talmud and commentaries by heart.

But his father had tuberculosis, and one day as he was studying the Torah with his 4-year-old, he suddenly coughed up a huge amount of blood, which covered the Torah page. His last words were, “Eliezer, my son, clean the Torah! Don’t bring dishonor to our sacred book.”

From that time on, the young child was sent to one religious boarding institution after another. He was always the best student wherever he studied. At one academy, his favorite rabbi slipped him a rare book that was not religious, but translated into Hebrew—Robinson Crusoe. It was that book that ignited his belief that Hebrew could be a living language once again.

In his memoirs, he wrote: “I fell in love with the Hebrew tongue as a living language. This love was a great and all-consuming fire that the torrent of life could not extinguish—and it was the love of Hebrew that saved me from the danger which awaited me on the next step of my new life.”

That next step came when he was slipped a short volume of Hebrew grammar by his favorite rabbi, who had dared to taste of non-religious books. Of course, his ultra-religious uncle with whom he lived was horrified that his nephew was straying into areas outside rabbinical literature, and in a rage, threw the 14-year-old boy out of his house, telling him never to return.

A Chance Meeting That Would Change History

Devastated, Eliezer wandered through the night to a nearby town, went into the local synagogue and fell asleep. A Jewish businessman, Solomon Jonas—more secular than traditional—approached him and invited him to his home. Eliezer was immediately drawn to his library, but found he could not understand a single word. The only alphabet he knew was Hebrew. Even his mother tongue, Yiddish, was written with the Hebrew alphabet.

Jonas took him in as a son. Recognizing his brilliant mind, the whole family participated in preparing him for an entrance examination to a state (secular) school, and after that, a university. Jonas’ daughter, Devora, was enlisted to teach him Russian and French—required for the state school. He taught himself mathematics and biology by reading books in his newfound languages. He excelled in school and made plans to attend university. Eliezer and Devora kept in touch by mail. Devora saw him as her prince.

Eliezer became very much a secularist, loving the great literary giants in Russian and French. No longer was he interested in Jewish things—except there was one thing he could not let go. He wrote, “That string was my love of the Hebrew language. Even after all things Jewish became foreign to me I could not keep away from the Hebrew tongue.”

A New Movement: ‘Nationalism’

Among the important events that lit a fire in this visionary was a rising “nationalist” movement among different peoples who wanted their own country. Eliezer saw how the Bulgarians were rebelling against their rulers, the Turkish Ottoman Empire, and he thought, If the Bulgarians, who are not an ancient, classical people can demand and obtain a state of their own, then the Jews, the “people of the Book” and the heirs of historic Jerusalem, deserve the same.

In the middle of the night, as he was reading newspapers, he said, “Suddenly, as if lightning struck, an incandescent light radiated before my eyes … and I heard a strange inner voice calling to me: ‘The revival of Israel and its language on the land of the forefathers!’ This was the dream.”

In the middle of the night, as he was reading newspapers, he said, “Suddenly, as if lightning struck, an incandescent light radiated before my eyes … and I heard a strange inner voice calling to me: ‘The revival of Israel and its language on the land of the forefathers!’ This was the dream.”

He then read a unique and controversial book by the famous author George Eliot in 1876, calling for a homeland for the Jewish people. That was the deciding factor that crystallized his mission for life.

He would go to Paris to study medicine and become a doctor. With that career, he would have a profession to earn a living for himself and his family. He planned to marry Devora, and they would go to live in Jerusalem.

His Catholic Confidant

Thus in 1878, Eliezer began his medical studies at the Sorbonne. He was penniless, but found an attic to rent and ate one meal a day. He spent his days studying in libraries across Paris. Visiting a Russian library, he met a new friend, a Russian/Polish Catholic journalist, Tchatchnikof, who promptly adopted him and opened for him the door to French literary society, introducing him to such literary giants as Victor Hugo.

Read the Whole Article

Do you find these posts helpful and informative? Please CLICK HERE to help keep us going!

In the middle of the night, as he was reading newspapers, he said, “Suddenly, as if lightning struck, an incandescent light radiated before my eyes … and I heard a strange inner voice calling to me: ‘The revival of Israel and its language on the land of the forefathers!’ This was the dream.”

In the middle of the night, as he was reading newspapers, he said, “Suddenly, as if lightning struck, an incandescent light radiated before my eyes … and I heard a strange inner voice calling to me: ‘The revival of Israel and its language on the land of the forefathers!’ This was the dream.”