by Zanne Domoney-Lyttle

Comic Books. Graphic Novels. Cartoons. Illustrated Pictures. The ‘Funnies.’ Methods of visual storytelling through sequential art have been around for centuries, yet this mode of narrative-sharing is often looked down upon, branded a lowly form of popular culture that is ‘just for kids’.

The label ‘just for kids’ is derogatory on three levels; firstly, children are inexorable in their ways of combining learning through fun, and that is nothing to be ashamed of. To suggest children’s literature is less important is to devalue the very education systems we pride ourselves on. Secondly, branding comic books as something that only the lower echelons of society can and should access, diminishes the amount of collaborative effort and work it takes to produce the things in the first place.

Thirdly, it does not take into account how comic books are often used as visual aids for learning in higher education institutions, as well as in homes around the world. In fact, you could argue that active modes of learning have frequently centred upon the combination of image with word to get its point across; pictures, as the saying goes, are worth a thousand words.

This is a concept that Bible illustrators have known for a long time. Consider, for example, the Garima Gospels, an illustrated Bible manuscript which dates back to the 5th-century CE. Biblical texts are incredibly difficult to read, understand interpret in some parts, so illustrating biblical texts was seen as a natural way to either clarify Scripture, or potentially fill in the gap between text and understanding. They are a form of visual exegesis if you will.

Post-publication of the Gutenberg Bible in the 15th-century, there was something of an explosion in the number of illustrated Bibles being produced. Ian Green argues that the reason biblical illustrations and illustrated Bibles grew in popularity at this time partly resulted from an increase in demand for visual aids as a well as a return to a more moralistic reading of Scripture, which meant readers wanted increased access to biblical texts.

Biblical illustrations were used either as visual aids to Scripture (for example, Biblia Pauperum which were printed block-books visualising typological narratives from the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament), and as decorative items to adorn the bookshelves of wealthy households. Poorer households were not left out of the picture-Bible trend. For the less-wealthy connoisseur of biblical illustrations, cut-and-paste sheets of biblical imagery were produced.

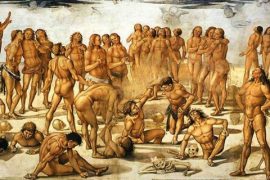

Wenceslaus Hollar (1607-1677) was one artist who produced such images. Born in Prague, a centre of arts, science and ambition in the early 17th-century, Hollar was a prolific artist who produced over 2,000 pieces of art, mostly in the format of etchings. Subjects varied from geographical and topographical scenes to portraits, fashion, visualizations of ancient and classic figures, and biblical motifs. On the last theme, Hollar produced visual interpretations of the classic stories of the Bible and drew inspiration from major figures such as Abraham, Moses, Jesus, and Paul.

Hollar produced two cut-and-paste sheets on biblical stories; one on Abraham’s story between Gen. 12-24 (see image below) and one on Jacob and Joseph (Gen. 25-48). Both are unsigned, untitled and undated. Cataloguer of Hollar’s works, Richard Pennington suggests that these prints were most likely produced as cheap, visual aids for the Bible reader, meant to be cut up and stuck in personal Bibles or to be used as a cheap and alternative way of decorating walls. The format of each image supports this – the grid-like pattern and the annotations to each image shows where to cut, and where to paste.

Do you find these posts helpful and informative? Please CLICK HERE to help keep us going!

7 Comments

Anyway, I have to be honest and say I hesitated looking at this post . Was concerned about a title like that. Just have learned to be very, very, filtering. You HAVE to be, to partake of something such as Facebook.

Glad I looked at this one, and yes, Illustrations are one of Thee best was to teach. The Jesuits used to do this with the Natives . And Jesuits are Known great educators.

Wether you think the Theology in Chick tracts is the best or not, a lot of people I have talked to simply liked to read them .

Terence said

Thanks T. I know I’ve seen this artistic style before, and that could be where from.

janitor9 said

It’s from a manuscript of Noah’s Ark from the Nuremburg Bible 1493. Don’t know the artist.

janitor9 said

Maybe the artist was just having some fun with that one…

Terence said

Be that as it may, it’s a pretty cool picture, and chock full of revelatory content from the Lord.

Is there any indication as to who the artist was, when it was drawn?

The "mer-dog" informs me that the artist was either fully inspired by the Holy Spirit to draw it – messaging the corruption of "all flesh", and/or that he/she had some knowledge of the Book of Giants, and/or Enoch, which informed what they drew. This would also explain the mermaids.

janitor9 said

And where did those evil Ondines come from?

And a Mer-dog? Waddup!?

I think what’s happening with these odd illustrations is that we have a modern expectation that

the artists were theologians. Instead, the artist probably struggled to even get access to any copy

of the text and what they created was based on limited understanding and word of mouth.

Can’t explain the Mer-dog, though.

And where did those evil Ondines come from?

And a Mer-dog? Waddup!?